Five Element Wellness Center

Assessment and Treatment of Neuropathic Pain

Assessment of neuropathic pain begins with a neurologic history, addressing the nature and onset of pain symptoms and underlying etiologic factors. Such factors include diabetes, alcohol abuse, vitamin deficiencies, environmental neurotoxins, trauma, structural lesions such as herniated nucleus pulposus or carpal tunnel syndrome, and inheritable causes.

To schedule a consultation, call one of the offices or book an appointment online.

Pain can be categorized into four mechanistic types: nociceptive, inflammatory, functional, and neuropathic. Nociceptive pain, a transient response to a noxious stimulus, performs a protective function to prevent tissue injury. Inflammatory pain, in which tissue damage causes both spontaneous pain and hypersensitivity, also has a protective function that may prevent further insults to an area of injury. In contrast, functional pain and neuropathic pain are maladaptive types of pain that are not a response to noxious stimuli or tissue injury. In functional pain, there is hypersensitivity due to abnormal central nervous system processing of normal peripheral sensory input. In neuropathic pain, the etiology is a lesion in the nervous system.

What Causes Neuropathic Pain?

Neuropathic pain may involve more than one mechanism of action. It may result from abnormal peripheral nerve function or neural processing of impulses due to abnormal neuronal receptor and mediator activity. Sodium channels may have altered expression, accumulation, or distribution. There may be increased expression of mRNA for specific neurotransmitters, such as substance P. Accordingly, no single agent may be efficacious for all neuropathic pain.

There are numerous targets for the pharmacologic treatment of neuropathic pain. In the peripheral nervous system, voltage-gated sodium channels, such as NaV1.7 and NaV1.8, have been found to be involved in various pain syndromes.4 Other diverse peripheral targets include calcium channels, the TRPV1 receptor, neuropeptide receptors, peripheral alpha-2 adrenoceptors, the TrkA neurotrophin receptor, and the P2X3 ATP receptor. Similarly, multiple targets exist in the central nervous system (CNS), including sodium and calcium channels, opioid receptors, the N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor, alpha-2 adrenoceptors, and serotonin/norepinephrine pathways.

Clinical Assessment of Neuropathic Pain

Assessment of neuropathic pain begins with a thorough neurologic history, addressing the nature and onset of pain symptoms and underlying etiologic factors. Such factors include diabetes, alcohol abuse, vitamin deficiencies, environmental neurotoxins, trauma, structural lesions such as herniated nucleus pulposus or carpal tunnel syndrome, and inheritable causes. The sensory phenomena of neuropathic pain manifest as both spontaneous pain (symptoms) and stimulus-evoked pain (signs). The latter may include positive signs, such as hyperalgesia, allodynia, hyperesthesia, paresthesia (burning, pricking), or dysesthesia. There may also be negative signs, such as hypoalgesia, analgesia, or hypoesthesia.5 Hyperalgesia and allodynia can manifest in response to both mechanical stimuli as well as thermal or chemical stimuli. Neuropathic pain patients suffer from spatial sensory abnormalities, such as dyslocalization, extraterritorial spread, and radiation of pain. They also may suffer from temporal abnormalities of after-sensation or abnormal latency.

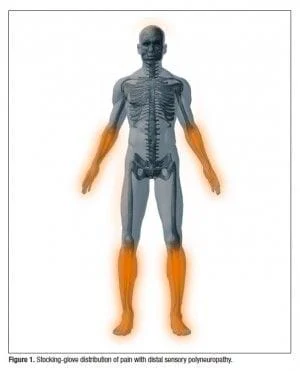

Evaluation of neuropathic pain symptoms (ie, spontaneous pain) can be performed using a variety of pain scales, inventories, and questionnaires. It is useful to have patients map the distribution of pain on a diagram of the human body, which can demonstrate characteristic patterns such as the stocking-glove distribution (feet/lower limb and hands/arm) of pain that occurs with a distal sensory polyneuropathy (Figure 1). Based on the identification of key words that might discriminate for neuropathic pain, a variety of screening tools have been developed, such as the Leeds Assessment of Neuropathic Symptoms and Signs (LANSS), the Neuropathic Pain Diagnostic Questionnaire (DN4), the Neuropathic Pain Scale (NPS), Neuropathic Pain Symptom Inventory (NPSI), and Neuropathic Pain Questionnaire (NPQ). These tools are based on verbal pain reports, and have limited to no need for bedside testing.

Physical examination for neuropathic pain includes evaluation of sensation (including provoked pain), motor function, and autonomic changes. Sensory examination helps confirm neuropathic pain and distribution and can uncover sensory deficits to various stimuli, including touch, pinprick, temperature, and vibration.6 Allodynia is assessed to determine if pain is provoked by static or dynamic stimuli, such as by light rub with a fingertip, cotton swab, or paintbrush (dynamic allodynia); or perpendicular pressure (static allodynia). Hyperalgesia is diagnosed if the patient has an exaggerated response to single or multiple pinpricks, or thermal stimuli such as a warm or cold test tube or tuning fork (thermal hyperalgesia). Summation (increasing pain to repeated stimulus) and after-sensation (prolonged perception of a stimulus after it is removed) are common during neuropathic pain. Muscle bulk, tone, and strength, as well as coordination and gait, should be assessed. Autonomic changes in limb temperature, sweating, skin color, or hair and nail growth may accompany neuropathic pain.7

Further diagnostic studies may be helpful in some cases of neuropathic pain.8 Blood tests or imaging studies may identify underlying causes of neuropathic pain or other abnormalities, such as rheumatologic disease or structural lesions. Electromyography (EMG) and nerve conduction velocity (NCV) also may play a role, but these studies are insensitive in acute injury and cannot assess the function of the small-fiber nerves that are involved in most neuropathic pain. These studies do not measure pain directly. Hence, normal EMG/NCV studies do not rule out a diagnosis of neuropathic pain, nor do abnormal results prove that pain is neuropathic.9 Small-fiber nerve function can be assessed by quantitative sensory testing, detecting abnormalities even when EMG and NCV are normal.

Neuropathic Pain Treatment

The management of neuropathic pain encompasses establishing a diagnosis, treating any underlying condition that may be causing the pain, providing symptomatic relief from pain and disability, and preventing recurrence. Neuropathic pain can be diagnosed as a specific entity, for example, as peripheral neuropathy or malignant radiculopathy.

When such specific treatment is not available or is not effective, symptomatic treatment should be offered. Treatment for long-standing neuropathic pain rarely eliminates the pain. Consequently, the following clinically meaningful goals should be established:

- Reducing pain

- Improving physical functioning

- Reducing psychological distress

- Improving overall quality of life

It is important for physicians and patients to have appropriate expectations for the outcome of treatment, knowing that it is unlikely that pain will be completely eliminated but that treatment can improve quality of life.13

In some cases, preventive measures should be addressed. Patients with diabetic neuropathy should seek to maintain tight glycemic control

(HbA1C <6). Patients with acute herpes zoster should receive early antiviral agents to prevent postherpetic neuralgia (PHN).

Treatments for neuropathic pain exist on a spectrum of invasiveness (Figure 2).14 On the low end of invasiveness are psychological and physical treatments, such as relaxation therapy and physical exercise programs. Next are topical medications, including lidocaine, capsaicin, and various custom-compounded topical agents of unknown efficacy. The next step includes oral medications—anticonvulsants, TCAs, opioids, and other agents, such as mexiletine or baclofen. Table 1, lists the agents that are FDA-approved for neuropathic pain. Finally, the most invasive treatments are interventional techniques such as nerve blocks, which are usually administered with local anesthetics and/or steroids. The efficacy of a treatment does not necessarily match its invasiveness, and a behavioral therapy or topical medication could be more effective than an interventional technique in a given patient.10,15 Treatments should be evaluated in terms of three important criteria: efficacy, safety, and tolerability.